A comprehensive look at the Tier 4 standards and how they affect landscape equipment owners and operators.

You purchase a piece of compact construction equipment, one manufactured after 2008.

Seated in the cab for the first time, you can have piece of mind knowing that officials say it ultimately plays into the prevention of 12,000 premature deaths, 8,900 hospitalization and 15,000 heart attacks each year by 2030.

But given that’s 15 years away, what you notice most, operating the machine in 2015, is what you’re sitting on in your back pocket—a slimmer wallet.

These facts and figures surround the Tier 4 standards, a government-mandated reduction in emissions from nonroad diesel engines that comes to fruition in 2015.

There are three parties involved with the regulations as they relate to the landscape industry: 1). Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which instated the standards; 2). equipment and engine manufacturers, charged with meeting the standards; and 3). you, the end user, who will—or may already—deal most with the new technology.

Here, we take a look at the standards from all three viewpoints to answer the question, “How does this affect landscape contractors?”

The gist, the impetus

Established by the EPA as part of the Clean Air Act, Tier 4 regulations were put in place to reduce emission of particulate matter (PM) and oxides of nitrogen (NOx), primarily in nonroad diesel engines.

Simply put, in diesel engine exhaust PM is the black smoke or soot. NOx, also found in exhaust, contributes to smog, which poses lasting environmental and health hazards.

With that, the end goal for Tier 4 is to decrease diesel engine emissions by more than 90 percent for health benefits—health benefits that could amount to $80 billion annually once all older engines are replaced, according to the “Clean Air Nondiesel Rule,” published by the EPA Office of Transportation and Air Quality (OTAQ) in May 2004.

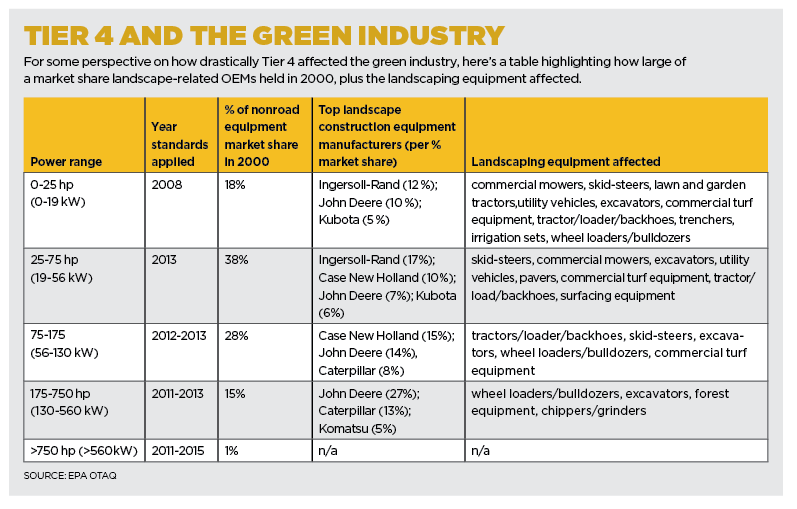

Under the Tier 4 standards, EPA categorizes nonroad diesel equipment into five power ranges—0-25 hp, 25-75 hp, 75-175 hp, 175-750 hp and more than 750 hp. The standards have staggered into effect for each category from 2008 to 2015 (see table), meaning manufacturers were barred from producing non-Tier 4 equipment and only selling equipment approved by the EPA as Tier 4-compliant.

There is no federal requirement for equipment owners to upgrade their units to Tier 4-compliant machines nor does the EPA have plans to put a rule in place, says Christie St. Clair in the office of public affairs at the EPA, OTAQ. In addition, manufacturers may still sell pre-Tier 4 units and replacement parts until their inventory is out.

St. Clair explains the No. 1 restriction to equipment owners is they may not disable emission controls on certified engines or equipment.

“Things have proceeded according to plan,” she says. “Once we adopt standards, manufacturers find optimal ways to meet standards. EPA has no significant role in that design process.”

There’s an expense, though, that comes with manufacturers having the creative freedoms to engineer products as they see fit—for manufacturers and end users.

And EPA recognizes that.

In fact, in 2004, it anticipated price increases for engines, equipment and fuel by 20 percent, 3 percent and 7 percent, respectively, under the standards.

“It’s going to vary depending on the application and what solutions the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) has taken as far as solutions,” says Jeff Wilke, product manager for diesel products, North America at Kohler Engines. “Things aren’t quite the same as they were previously. There’s a bit more componentry.”

The manufacturers’ challenge

There are two common solutions for reducing NOx and PM emissions in diesel engines, Wilke says. Both involve after-treatment devices—removing diesel particulate filters (DPFs) and/or introducing selective catalytic reduction (SCR) to an engine unit.

Kohler Engines has taken the route of nixing DPFs.

“We started with a brand new engine design from the ground up,” Wilke says.

A DPF, he explains, consumes fuel to burn off PM. Eliminating that offers “proven fuel savings, better fuel economy, better throttle response and more torque for a similar size engine.” Plus, there’s less maintenance on an engine if there’s no DPF to be serviced.

Thus far, Kohler has engineered engines up to 75 hp. As it continues to grow its engine division, tapping into more than 75 hp, Wilke says it likely will approach those units with SCR, an additional catalyst in the exhaust that involves an injection of urea.

To further reduce PM, Tier 4 engines can use only ultra low sulfur fuel (ULSF), too, the only highway diesel fuel available in the U.S.

As Greg Knott puts it, sulfur can “poison aftertreatment systems.” Using ULSF means engines must have “sophisticated catalytic converters,” says the director of industry affairs at the Outdoor Power Equipment Institute (OPEI).

How all this translates to OEMs, they “want to know what technology will be used, how exhaust temperatures will be impacted and how much it will cost,” Knott says.

Take Caterpillar, for instance. The manufacturer has sold nearly 200,000 Tier 4 products, says Jeromy Myers, marketing consultant for Tier 4 migration at Caterpillar.

“Caterpillar recognized early on that one technology solution would not fit every application,” he says. The OEM focused on how the engine changes would affect equipment operators’ day-to-day activities.

“The only change our customers should experience is the need to refill the Diesel Exhaust Fluid tank every time they refuel their machine,” Myers says, adding Caterpillar also has recorded lower owning and operating costs for its Tier 4 equipment compared to previous generations.

For other OEMs, curbing consumer costs on Tier 4 equipment has been a challenge.

But it’s not without reason that some are making end users pay for the changes, Knott says.

Stiffer standards possible

Simply put, “The engines are getting better,” Knott says. “The technology coming out now can make some pretty big improvements in efficiency and performance over a similar engine with mechanical fuel injection.”

He adds that having Tier 4 equipment could give contractors an edge in bidding processes if prospects take emissions into consideration.

And in some locations, they may even be required to have such equipment.

In California, for instance, manufacturers must certify products with the California Air Resources Board in addition to being certified with the EPA. Any state and local government may regulate the use of and operation of engines and equipment without EPA’s consent, St. Clair says.

Wilke expects larger cities and other states to have a heavier hand in local regulations moving forward, especially as talk of “Tier 5 is on the distant horizon.”

St. Clair somewhat cleared the air on that possibility, though.

“The European Union is exploring the equivalent of Tier 5 standards for nonroad diesel equipment,” she says. “There are no current plans for EPA to pursue such standards.”

Still, Wilke says manufacturers are preparing for the prospect of stiffer standards by changing the perception of horsepower.

The reality, he says, is many equipment owners view horsepower as power. Manufacturers need to prove smaller horsepower products can deliver adequate torque. If not, we could see a turn to alternative solutions for diesel engines, Wilke says.

“Diesel engine use is already limited in outdoor power equipment,” Knott adds. “It will be interesting to see how many engines and applications move to gasoline due to the costs related to the regulations.”