Brown patch and large patch are some of the most damaging diseases of cool-season and warm-season turfgrasses. Summer patch is another devastating disease. To properly diagnose and treat these diseases, let’s reference NC State University Extension’s Turf Files.

Brown patch

In landscape situations, where mowing height is greater than 1 inch, brown patch appears as roughly circular patches that are brown, tan, or yellow in color and range from 6 inches to several feet in diameter. The affected leaves typically remain upright, and lesions are evident on the leaves that are tan in color and irregular in shape with a dark brown border. When the leaves are wet or humidity is high, small amounts of gray cottony growth, called mycelium, may grow in affected leaves.

Brown patch is most severe during extended periods of hot, humid weather. The disease can begin to develop when night temperatures exceed 60 degrees F, but it is most severe when low and high temperatures are above 70 and 90 degrees F, respectively. The turfgrass leaves must be continuously wet for at least 10 to 12 hours for the brown patch fungus to infect. Poor soil drainage, lack of air movement, shade, cloudy weather, dew, overwatering and watering in the late afternoon and prolonged leaf wetness can increase disease severity. Brown patch is particularly severe in turf fertilized with excessive nitrogen. Inadequate levels of phosphorus and potassium also contribute to injury from this disease.

Large patch

Large patch, is a new name for an old disease of warm-season turfgrasses. This disease was called brown patch, but some differences distinguish this disease. Different strains of Rhizoctonia solani produce distinct summer patch symptoms and require very different control strategies.

Large patch begins to develop when soil temperatures decline to 70 degrees F in the fall, but the symptoms do not necessarily appear at this time. The symptoms of large patch are most evident during cool, wet weather in the fall and spring. In many cases, symptoms may not become apparent until early spring when warm-season grasses green up.

Excessive fall and spring nitrogen favor large patch, as well as poor soil drainage, overirrigation, excessive thatch accumulations and low mowing heights. Centipedegrass and seashore paspalum are most susceptible to large patch, followed by zoysiagrass and St. Augustinegrass. Bermudagrass is rarely affected by large patch.

Summer patch

This hot-weather disease occurs on annual bluegrass, Kentucky bluegrass and fine fescues. The symptoms of summer patch appear in circular patches or rings ranging from 6 inches to 3 feet in diameter. Turf within these patches is initially off-colored, prone to wilt, growing poorly or sunken in the turf stand. The turf continues to decline for one to two weeks, turning yellow or straw brown and eventually collapsing to the soil surface.

You can easily pull up affected plants from the turf, revealing black and rotten roots, crowns, and rhizomes. The patches recur in the same spot annually and expand at 2 to 4 inches annually. The disease attacks the plant in the spring when soil temperatures reach 65 degrees F. Summer patch is most severe when soil pH is 6.5 or greater and excessive nitrogen in the spring and overirrigation encourage development.

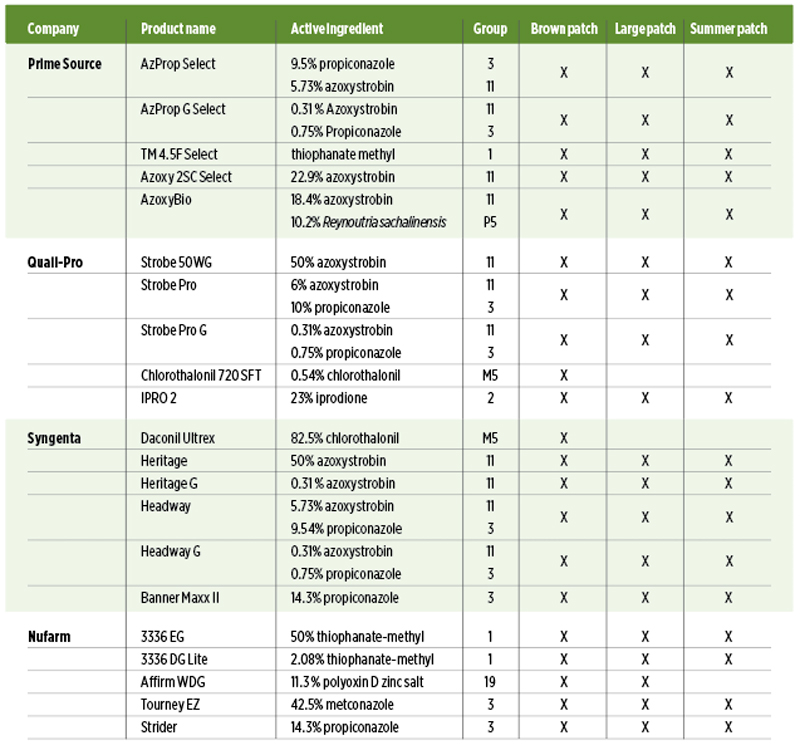

Several fungicides that control these three patch diseases include propiconazole, azoxystrobin, thiophanate methyl, iprodione, chlorothalonil and metconazole (See Table 1).