With the recent heat waves that hit the eastern U.S. at the end of June, many have been worried about just staying cool and out of the sun. But for lawn care operators (LCOs) and turf pros, the dog days of summer also come with a slew of turf-related issues, too.

Drought, heat stress and fungal diseases can all sprout from the warm weather, but one of the most troublesome issues is gray leaf spot (GLS). This disease (Pyricularia grisea) is especially common in turfgrasses like perennial and annual ryegrass, tall fescue and St. Augustinegrass. Plus, warm, humid places such as the transition zone, mid-Atlantic regions and even the Midwest are particularly susceptible.

“We tend to see it when we hit the 160 degree (F) cumulative temperatures (day and night),” says Jay Wyrick, turf and ornamental agronomist at FineTurf in North Carolina. “It’s already in the high 90s here … then, when you get some rain or irrigate at the wrong times of the day, you’re going to start seeing problems.”

One reason GLS is such an issue is due to how quickly it can destroy a lawn, Wyrick says. The fungus produces spores on infected leaves, which can spread through wind, rain, foot traffic or lawn equipment.

“It can absolutely decimate a yard in about two weeks in a tall fescue lawn. I mean, it can really, really coalesce quickly,” he says.

Spot it fast

While Wyrick says the disease can sometimes be confused with drought or “melting out” to the untrained eye, GLS should usually stand out pretty quickly.

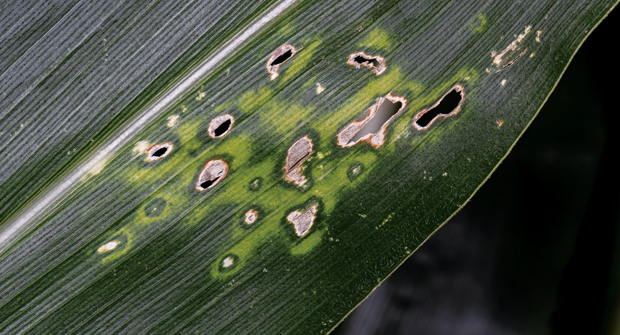

The leaves will show circular or oval tan spots with dark brown borders, something Wyrick says can be compared to chicken pox. The spots can also become gray and fuzzy due to spore production in humid conditions.

Patches of affected turf often become noticeably thin from dead and decaying leaf blades if left untreated, and due to the speed of GLS’ spread, quick identification is critical.

Finding new solutions

For Wyrick, his GLS control consists of common fungicides such as thiophanate-methyl (T-meth) and azoxystrobin.

“That gives us a little better protection as a combo,” he says, recommending a quick, proactive approach to applying fungicides when the disease starts appearing.

Another tip during prime GLS conditions is to stop mowing as much. Wyrick says the turf isn’t growing as quickly during the hot summers, and the constant mowing can further move the spores around while also damaging the turf’s tissue.

“I do see some issues with guys that mow on a weekly basis and get paid for weekly mowing — they can tend to cause a bigger problem with (spores) by moving them around,” he says. “We try to tell people, when it gets to 90 degrees with tall fescues, not to mow every week.”

To help rely less on chemical control, Wyrick says he’s started looking to improve his turf through GLS-resistant seeds, adding that many seed producers are starting to develop genetically improved grass varieties that can better withstand diseases.

“We know we can’t out-pesticide insects and diseases, so we’re trying to have better genetics in our turfgrass seed that we get for the fall,” Wyrick says. “When we go to aerating and seeding, you have several turfgrass varieties now that are gray leaf spot resistant or have more resistance to gray leaf spot.”