Editor’s note: When the rains fail, lawmakers and agencies too often react with watering restrictions or, in the most drastic cases, watering bans rather offering incentives and developing other programs to encourage conservation. That’s been the case in much of the Southeast the past two years, and it’s been a huge challenge to any business involved in the green plant business there.

We start our three-part investigation of water issues with challenges faced by Atlanta, and we look at one example of a company in the West that’s learned to deal with drought in a profitable way.

Consensus conservation

Chicago-based Alliance for Water Efficiency is poised to lead North America to a more sustainable use of its fresh water resources.

The Alliance for Water Efficiency (AWE) became active in September 2007. In that respect, it’s in its infancy. But it’s also well on its way to igniting a broad-based effort aimed at boosting the efficient and sustainable use of North America’s fresh water resources.

Mary Ann Dickinson |

The AWE, headquartered in Chicago, intends to be the organization “pulling everybody together” toward a sustainable water future, says Executive Director Mary Ann Dickinson.

And when she says “everyone,” you can almost take that literally.

“We put together a stakeholder discussion process,” says Dickinson, noting that it led to the formation of the 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. “We held workshops and focus groups with industry leaders. We asked them, ‘What do you need to participate in water efficiency more actively?’ They said they needed a national organization to coordinate them. They said they needed a non-profit to represent every stakeholder group.”

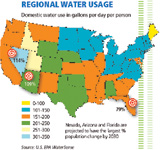

Regional water usage |

A 23-member board of directors guides the AWE. Two board members — Warren Gorowitz, national water management products sales manager, Ewing Irrigation Products, and Ron Wolfarth, director of Rain Bird Corp.’s landscape management division — are from the irrigation industry. The other 21 board members represent a diverse group of public and private organizations, including water utility officials, conservation managers, academics and private industry, among others.

“We want to achieve our goals with input from all sides,” says Dickinson, who has worked with water issues for 35 years prior to founding the AWE.

Dickinson lists water shortages, the cost of providing additional supplies of potable water, continuing urban development and population growth, and the need for more efficient landscape irrigation, as among the largest water challenges facing North America.

Keeping up with growth

Between 1950 and 2000, the U.S. population doubled — but the demand on public supply systems more than tripled.

In a 2003 U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) survey, 36 of the 50 states predicted water shortages by the year 2013. Several Western states didn’t even respond to the survey because their shortages were already so obvious.

“That’s 40 of the 50 states looking at shortages of fresh drinking water supply shortages,” says Dickinson.

The states base their predictions on growing demand for fresh water, much of that demand coming from population growth and development.

“We may be in an economic downturn, but we’re still growing. We’re still building houses,” says Dickinson. In fact, she refers to a study by the Brookings Institution that forecasts that more than half the houses that will exist in the U.S. by 2030 have yet to be built.

Developing additional supplies of fresh water will be incredibly expensive. The cost of building the infrastructure to accomplish the goal has been estimated at $533 billion, she says, pointing to a recent government study. Even small gains in water conservation can translate into huge cost savings, she adds.

“If we could save 1% of demand and 1% of that capacity, that’s $5.3 billion (on) that infrastructure bill,” she says.

Some of that savings must come from landscape irrigation, which accounts for 30% to 60% of urban water consumption, depending upon the region of the country.

Dickinson says that educating homeowners to proper irrigation practices, promoting and using smart watering technology and implementing strategies such as water audits and water budgets can achieve measurable outdoor water savings.

“Water is too cheap,” she says. “The energy crisis has done a lot to make sure people are conserving energy. With water, we’ve always had subsidies. Those subsidies mask the true cost of supplying and distributing that water.”

The AWE is a membership-driven organization, Dickinson stresses. To learn more about it, visitwww.allianceforwaterefficiency.org.

Bruised, but water wiser

The Atlanta-area Green Industry took a big hit when Georgia turned off irrigation last year, but owners say they’re now better prepared to deal with water issues.

The rain will return. The reservoirs will refill. A section of the Southeast stretching from Alabama to the Carolinas wilted by a lingering drought will become green again.

But the questions this once-in-a-century dry spell have spawned need answers:

- Will state and regional leaders develop and follow through on plans to increase the region’s water capacities?

- Should water authorities offer incentives to property owners to encourage more efficient irrigation?

- Will property owners be willing to accept dormant turfgrass? Will they learn about and ask for drought-resistant ornamentals in their beds?

- How committed are Green Industry professionals to providing clients with water-efficient landscape designs, educating clients on best water-conserving strategies, and offering value-added and not “value-engineered” irrigation installation and ongoing professional maintenance and repair services?

- Will water-conserving concepts such as rain gardens, rainwater harvesting, permeable paving and plant zoning gain more widespread acceptance within the Green Industry?

Whew. If all of this seems too much to hope for from a single drought, maybe it is. But let’s take the high road.

Watering southern lawns |

Rick Upchurch, president of Nature Scapes, Lilburn, GA, is indicative of the progressive stance that many professionals have taken in the face of drought and ongoing irrigation restrictions.

“If we choose to be a little more creative, and agree to make a few simple changes, we will be less affected by the water restrictions placed upon us and still enjoy the colorful landscapes we have learned to appreciate,” he says.

Rick Upchurch |

In his company’s case, “creative” means recommending for clients’ landscapes more drought-tolerant flowering plants such as lantana, vinca, wave petunias, portulaca, vebena and scaevola. It means suggesting that clients replace their fescue lawns with Bermudagrass, which requires less water to remain green. It means using surfactants to break the soil’s surface tension, allowing water to reach plant roots more easily. It also means using gels that release water over a period of time for trees, shrubs and containers.

Few people in northern Georgia appreciate their fresh water resources or irrigation more than Ed Klaas, president of the Georgia Irrigation Association.

Ed Klaas |

This particular summer morning, Klaas is surveying his 11-year-old Volvo in a Chick-fil-A parking lot in Roswell, GA. Klaas is on his way to his business, Southern Sprinkler Systems.

“This is another of my contributions to water conservation,” he says, grinning good-naturedly as he points to the dust and dirt covering his car. Klaas hasn’t washed it for months. He seems almost proud of its appearance.

Asking too much of the ‘ HOOTCH’? |

Many other business owners have also quit washing their trucks. They fear customers may see spotless service vehicles (formerly the mark of a “professional”) as a waste of water.

This is among the smallest sacrifices most Atlanta-area Green Industry companies are making in response to the drought, and especially to the unprecedented announcement this past Sept. 28 banning outdoor watering of established lawns and landscapes. (Newly installed landscapes got a 30-day watering window.)

Irrigation in residential water use |

Predictably, the decision by the Georgia Environmental Protection Division (EPD) had an immediate negative effect on just about every aspect of the Green Industry. It had the greatest impact on plant nurseries, professional installers of living plant material and irrigation contractors.

Terry England |

The ban, coming when it did, slammed the installation of new lawns and fall seasonal plantings. Atlanta’s reputation as the leading “color” market in the Southeast wilted as customers’ requests for flowers and annual color dropped. Why plant if you can’t keep turf or ornamentals alive, they reasoned.

Klaas’ irrigation company suffered like all the others. When the calls stopped and orders were canceled, he was forced to lay off almost all of his field technicians.

Thirsty grass |

“I broke down,” he recalls. “That was a hard, difficult day.”

Other Green Industry companies had equally difficult calls. Nobody knows for sure how many operations called it quits, but two of the most visible victims of the drought included 36-year-old Charmar Flowers and Gifts, Athens, GA, which closed its doors at year’s end, and Pike Family Nurseries, Atlanta, which filed for Chapter 11 protection in November. The 50-year-old, family-owned Pike had grown into a popular regional institution, with about 500 employees in multiple locations.

In its September announcement of the watering ban, the state EPD pointed to low-stream flows and reservoirs at historically low levels for its decision.

Especially troubling to state officials was the dropping level of Lake Sidney Lanier, located about 40 minutes northeast of Atlanta. Lake Lanier is a 38,000-acre lake with a shoreline dotted with homes, boat docks and beaches. It’s the main source of drinking water for Atlanta. The Chattahoochee and Chestatee Rivers feed Lanier. (See “Asking too much of the ‘Hootch’?” below)

Precipitation this past winter and spring did little to rejuvenate the lake. And this past spring, the Army Corps of Engineers admitted that it had mistakenly released too much water from the lake to maintain downstream flow. Lanier remained at a record 14.4 feet below full as this summer began.

The low lake level is not a new phenomenon. And while everyone knows the rains will return, nobody can predict when.

Indeed, a day after Georgia Gov. Sonny Perdue led a public prayer for rain this past November on the steps of the Capitol, the rain did return. One inch.

“We can’t conserve our way out of this drought,” says Klaas. “We have a water storage and capacity problem. We need more reservoirs and more capacity.”

The Green Industry reacted to the news of the September ban with a flurry of information for the local media and the public. It also redoubled its lobbying efforts at the state capital. The 2-year-old Georgia Urban Agricultural Council (UAC), a coalition of six regional Green Industry associations, led the charge.

Although northern Georgia did get some precipitation this past winter, it wasn’t enough to ease the drought. Even so, industry lobbying had some effect. In late February, Perdue relaxed watering restrictions to allow evening and early-morning hand watering of landscapes, and three-days-a-week watering for those newly installed.

A political ally

State Rep. Terry England (R-Auburn) is proud of his farming background. Two blue Future Farmers of America (now the National FFA Organization) jackets hang on a coat rack behind his desk in his office in the state office building downtown. “I’m an adviser,” he says, turning to the jackets.

England also runs The Homeport Farm Mart in Winder, GA, a city of about 10,000 people in rural Barrow County just east of Atlanta. His family business sells flowers, vegetable plants, seeds, fertilizer and just about anything else you would need for a garden.

“We don’t have a problem with the amount of water we get or its use,” says England. “We have a problem with storage and with retention.

“We know that every inch of rain that falls on our state amounts to 1 trillion gallons of water,” he continues. “We usually get about 54 inches a year. That means 54 trillion gallons of water.”

England says one of the biggest flaws with the September 2007 watering ban and the pronouncement by Gov. Perdue a month later seeking a further 10% reduction in water use for northern Georgia communities was its blanket approach.

“We had counties and cities within the drought declaration that have more water than they knew what do with, but they were unable to sell it,” says England. The ban caused their revenues to fall, creating havoc on water department budgets and delaying vital municipal capital-improvement projects.

England turned out to be just the person the Green Industry could count on to get some legislative relief.

Supported by the Georgia UAC, the Georgia Agribusiness Council and the Georgia Farm Bureau, England this past spring successfully championed HB-1281. The new law creates one statewide standard for water restrictions during times of a drought, and prevents local governments from adopting water-use restrictions stricter than those of the state unless approved by the EPD.

England says the law expires in 2010, giving the state time to develop a new, comprehensive drought plan.

“The continued availability of fresh water is the single largest challenge to Atlanta’s continued economic growth,” he says.

Making the best of it

Dave Price and his business partner, David Bennett, offer “Southern Gardens, European Detail” through Bennett Design & Landscape.

Price says his company is concentrating on selling and building hardscapes. When the drought eases, it will concentrate on plant installations again.

“We tell clients, ‘Let’s get the construction out this year. We’ll do the hard work, the messy work, and then we’ll do the rest of the project when restrictions ease up,'” he says.

Price says that calls for plantings dropped dramatically in the fall of 2007, but rebounded somewhat this past spring. He says he believes the relentless media publicity surrounding the drought, especially in 2007, had a lot to do with demand for new landscapes and installations falling so steeply last year.

In response, he says his company alerted customers to low water-use plants and, in many cases, used polymers in the bed planting mix to help the soil retain moisture.

“Everyone is used to seeing lots of seasonal color in this market,” adds Price. “That’s not going to change, and until this drought is over I think everyone in this business is just going to have to tighten their belts and get smarter about water use and about their costs.”

inding opportunities in a drought

Refusing to let business dry up in the face of a historic drought, this Denver company rolled out valuable new services to save customers’ trees and turf.

The summer of 2008 will go down as one of the hottest and driest ever recorded in Colorado. Even so, property owners serviced by Denver Water are being allowed enough water to keep their landscapes green and healthy. The region’s reservoirs remain full or nearly full, thanks to adequate mountain snowmelt, the source of water for the 1.1 million residents served by the utility.

John Gibson |

This is a far cry from 2002 and 2003, when severe drought caused a welter of watering restrictions as Denver and surrounding communities on the Front Range sought to conserve fresh water. These restrictions created daunting challenges for anybody involved with growing, selling, installing and maintaining turfgrass and other landscape plants there.

It also created great opportunities, one progressive company discovered.

At a glance |

The management of Swingle Lawn, Tree & Landscape Care, recognizing in 2002 that water availability would always be a challenge in its semi-arid market (average annual precipitation of 15.8 in.), began brainstorming to see what services it could provide customers to protect their landscapes.

“We went through a complete process of identifying potential services,” explains John Gibson, director of operations. He calls the result “an opportunities checklist.”

“I put together this simple spreadsheet, and we rated the ideas we came up with,” he explains. The process involved assigning a value to each of a range of factors to consider for each potential new service — customer needs, equipment required, manpower, technical expertise and profit potential.

After Gibson and his team tallied the scores, they identified a dozen drought-inspired services they believed they could offer profitably. Near the top of the list was a supplemental tree/shrub watering service.

Swingle management realized that many customers feared losing trees and other valuable landscape plants to drought, so they sent out a direct mail marketing piece to announce ReCharge, the company’s new deep-root watering service. During that winter and spring, Swingle converted its tree and lawn spray vehicles to carry water.

The level of positive customer response surprised even Gibson. Swingle soon purchased more trucks to meet demand. By the winter of 2003-2004, the service was going full blast.

Win-win for everyone

The deep-root watering service has been successful on several fronts, including keeping company revenues at an acceptable level during the off-season.

From a customer standpoint, it has proved its worth in keeping trees and shrubs healthier. This became abundantly clear during March 2003, when a late-winter storm buried the region. Many trees and shrubs that had not received supplemental watering during the dry winter were badly damaged or destroyed by the unusually heavy wet snow.

“The weight of the snow just snapped off their limbs,” recalls Gibson. “They were crisp from the drought.”

Demand for the watering service fluctuates considerably from winter to winter, depending upon precipitation.

Realizing that droughts stress trees, turfgrass and other landscape plants, and make them more susceptible to insect pests, in particular, gave the company another opportunity to offer customers special services.

Swingle stepped up its pest control services to combat destructive insects such as the mountain pine beetle and turfgrass-damaging Banks grass mites. Because mites can become a nuisance inside homes, as well, the company also began offering perimeter pest control.

A lesson learned

Of the 12 services the company identified as new (and potentially profitable) during the 2002 drought, nine remain.

That particular drought also served up a sizable helping of irrigation education for the company and its many customers, says Gibson.

“It taught us to be better water managers,” he says. “We discovered we were overwatering — and overwatering a lot.”

That realization prompted the company to more strongly promote watering efficiency to customers, and to strengthen its irrigation services, including installing products such as smart controllers and rain sensors.

Gibson says he believes the region has a much better understanding of its unique fresh water challenges as a result of its drought experiences. But as long as Front Range communities continue to grow, the availability of fresh water will also grow as an issue there. And it will require even more creativity and cooperation to maintain the region’s special lifestyle.

Water done right

Smart water use starts with proper landscape design, soil preparation and installation and solid cultural practices.

Research has shown that a properly planned landscape that has been carefully installed and properly managed will be healthier, less prone to insects and diseases and will require less irrigation.

For ornamentals or trees, apply 3 in. to 5 in. of mulch on the soil surface after planting. |

Consider the following strategies in providing clients with water-conserving landscapes.

Test the soil. A soil test tells you how to improve the soil to enhance plant nutrient uptake. Testing is available through county extension offices and some retail garden centers.

Where’s the water? Identify your primary source of water (municipal, well, surface) and explore alternative ways of obtaining water for irrigating plants, such as rainwater harvesting and storage; collection of air-conditioner condensate; and rain gardens.

Put the right plant in the right place. When selecting plants for your landscape, make lists of the plants based on their water needs (low, medium or high) and sunlight requirements. By doing so, you are grouping plants with similar water and light needs in the landscape.

Use the land wisely. Place plants with lower water needs at higher elevations and plants with higher water needs in flat areas or at lower elevations. Irrigating sloped land will result in less efficient irrigation (higher runoff and erosion). Also, catalog sunlight patterns: Place sun-loving plants where they get six to eight hours of full sun, and shade-loving plants where they will be shaded from the hot afternoon sun.

Proper planting matters

Soil amendments are key. Organic amendments improve the physical and chemical properties of the soil. They not only help the soil hold water and nutrients, they also improve water movement throughout the soil. Incorporate 2.5 in. to 4 in. of organic amendment (compost) to a maximum depth of 8 in. to 12 in.

Mulch, mulch, mulch. For trees or ornamentals, apply 3 in. to 5 in. of mulch or compost on the soil surface after planting. Mulch not only conserves water, it also maintains a uniform soil temperature and reduces weeds that compete for light, water and nutrients. Fine-textured mulches and/or compost prevent evaporative water loss better than coarse-textured mulches.

Water it in. Watering is a key part of the planting process. First, water the plants in their containers just before planting. Set the container on the turfgrass or planting bed so that any excess water draining from it benefits the landscape. Add additional water to settle the soil and eliminate air pockets as you fill the planting hole with soil. Finally, water again after planting. These three steps reduce planting shock.

Be careful around established plants. Avoid digging under established trees or shrubs and injuring their roots. It’s estimated 80% of the roots of established trees and shrubs are within 12 in. of the soil surface. Fill dirt or topsoil added over the roots of established plants can smother the roots and cause stress.

Prune those roots. If you remove the plant from the pot and see a mass of tangled roots, use a knife to make four to six vertical cuts around the root ball, then pull apart the roots. This encourages new roots to form, allows water to move into the root ball and results in more rapid plant establishment.

Water-saving management

Use your eyes. Watch for moisture stress symptoms before irrigating. An abnormal gray-green color and/or obvious wilting are good indicators that a plant needs moisture. Watering plants only when they require results in a deep, strong root system that conditions the plant to tolerate dry periods.

Timing is everything. The best time to irrigate is at night or early morning to conserve moisture and to reduce evaporative losses of water.

Test the soil (again). A soil test provides the best gauge for fertilization requirements in the landscape. Healthy plants are more water-efficient during dry periods. Never fertilize according to the calendar; instead, base it on the needs of the plants and nutrient levels in your soil.

Know your fertilizer. Slow-release-type fertilizers and compost release nutrients slowly over time, resulting in more uniform growth rates and more water-efficient plants. Excess nitrogen causes rapid growth and increases water demands.

Keep the mulch coming. Maintain an average depth of 3 in. to 5 in. This may require you to add 1 in. to 3 in. of additional mulch each year. Maintaining a uniform layer of mulch over plant roots is one of the best water-conservation practices for your landscape.

Toughen your turfgrass. When properly planted and managed, turfgrass is more resilient to periodic drought conditions than many people assume. Regardless of drought conditions, allow the grass to dry and become stressed before applying irrigation. This causes the grass plants to explore deeper soil depths for moisture and nutrients. Periodically aerify to improve water and air entry into the soil. To encourage deep rooting during periods of heat or drought stress, raise the mowing height to the upper limits of recommended mowing heights.

Where is the water going? To avoid wasting water, use a handheld hose, soaker hose or drip irrigation to water trees, shrubs and flowers, especially those on slopes. Water only the soil, not the leaves and flowers. To avoid runoff, apply water gently and slowly at a rate the soil can absorb. When using sprinklers, make sure that the water reaches only your lawn and plants — not the house, sidewalk, driveway or street. Retrofit your irrigation system with low-volume emitters and a rain sensor that will prevent it from running during rainfall.

Acknowledgement: The University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences

In our September and October issues we’ll focus on other regions of the United States and how contractors there are meeting water challenges while providing valuable landscape services. We’ll also look at the national Irrigation Association and its role in educating and leading the industry, the U.S. EPA’s WaterSense program, the Green Building Council’s LEED. We’ll also examine Australia Water Smart and its ambitious and innovative approach to water conservation.